How to Quantify Risk

There has been much criticism of risk assessment and analysis over the past few years that amount to much ado about nothing. Why is it much ado about nothing? Well, because, quite simply, people oftentimes don’t understand what it is they’re criticizing, especially in the case of quantified risk analysis methods.

Before we get into risk measurement, let’s first make one thing clear: risk analysis is nothing more than a decision-analysis (or decision-support) tool. It helps provide reasonably accurate data points that decision-makers can use when make decisions. It is not a panacea for all things risk or infosec, nor is it some sort of special magic-sauce voodoo with no grounding in reality (at least not in terms of well-considered quant methods). Clear? Crystal, I’m sure. 🙂

When performing a risk analysis, we need to start with the basics. Here at Gemini we subscribe to the Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) methodology for performing quantified risk analysis. FAIR defines risk as “the probable frequency and probable magnitude of future loss.” What this means in real terms is that FAIR reduces “risk” into two main components: Loss Event Frequency and Loss Magnitude. Both are estimates that are created using Douglas Hubbard’s calibration technique, as advocated in his book How to Measure Anything.

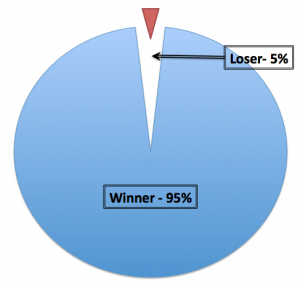

Hubbard’s approach to measurement is quite simple: start with a range of values and then ask “If I had to choose a winner between my range and spinning a wheel with a winner space covering 95% of the wheel, which would I pick?” (see an example of said wheel at right). Your initial ranges should select absurd endpoints such that you’ll definitely choose the range. However, as you begin to narrow the range, you should then get to a point where you are indifferent between the range and the wheel. If at some point you’d pick the wheel over your range, then you need to adjust an endpoint accordingly. In the end, our range can be said to be “accurate” because the most likely value falls within our estimate. The narrower our range is, the more precise our estimate is.

Hubbard’s approach to measurement is quite simple: start with a range of values and then ask “If I had to choose a winner between my range and spinning a wheel with a winner space covering 95% of the wheel, which would I pick?” (see an example of said wheel at right). Your initial ranges should select absurd endpoints such that you’ll definitely choose the range. However, as you begin to narrow the range, you should then get to a point where you are indifferent between the range and the wheel. If at some point you’d pick the wheel over your range, then you need to adjust an endpoint accordingly. In the end, our range can be said to be “accurate” because the most likely value falls within our estimate. The narrower our range is, the more precise our estimate is.

In this manner, we can then go about producing estimates under Loss Event Frequency and Loss Magnitude. Let’s start with the “easier” concept first: impact. Under the FAIR methodology, we estimate both primary and secondary impact. Primary impact is often straightforward to estimate, and has a higher degree of precision than secondary impact, which by its very definition will have a wider range of potential outcomes. These impacts are further broken down into categories, such as Productivity or Replacement.

On the other side of the tree, we divide Loss Event Frequency into two components: Threat Event Frequency and Vulnerability. In this case, we define vulnerability as “the probability that threat force will exceed resistance strength.” Vulnerability is not, then, used in the traditional infosec lingo use case where it describes a weakness, but instead looks at the capability of a threat agent and the general resistance of an asset to attack.

Finally, Threat Event Frequency is where a lot of the controversy in risk analysis arises. Some argue that there are too many “unknown unknowns” in the world to allow us to make a reasonable estimate around a given threat event. However, this criticism fails to understand how a methodology like FAIR operates. In setting up your risk analysis, you will define a specific asset profile, including whether you’re most concerned with confidentiality, integrity, or availability. You’ll also then define a specific threat agent profile, such as “casual hackers” or “script kiddies” or “professional hackers” etc. However, you’ll go even deeper in defining the threat agent, breaking down this Threat Event Frequency value into an estimate of Contact Frequency (the likelihood that the threat agent will make any sort of contact) and an estimate of the Probability of Action (the likelihood that a threat agent will act against your asset).

There are a few potential weaknesses with these probability estimates. For example, we know that there are likely many cases where professional hackers (organized criminals or nation-state actors) are making contact with an organization and not being detected. Similarly, we may over- or under-estimate the probability that a threat agent will act against us. We can, however, address some of these issues through a couple key approaches. First, if we’re having difficulty defining reasonable ranges, then we need to ensure that our threat agent profile is sufficiently constrained, even if that means starting a second analysis on a separate profile. Second, we need to ensure that our ranges are broad enough to be reasonably accurate before we work to narrow them to an adequate degree of precision.

In the end, having some real-world data, either from aggregate reports or from our own internal infosec programs, will go a long way toward helping refine these estimates. We know that certain events are happening on a regular basis. We know about a wide variety of threat agents who can be reasonably defined and described. And, again, risk analysis tools like FAIR are design to support decision-making, not to replace it altogether. If the results feel wonky, then it’s likely something is off and the numbers need to be re-evaluated. Ultimately, you simply need to ensure that your decisions are well-reasoned, reasonably defensible from a legal perspective, and that they demonstrate a reasonable degree of foreseeability.

Interested in learning more about FAIR? Please let us know!

One thought on “How to Quantify Risk”

Comments are closed.